Massive meat-eating dinosaur that was biggest to ever live hunted underwater

An analysis of the marine monster's bones has found it was adapted for an aquatic lifestyle.

Published

2 years ago onBy

Talker News

By Mark Waghorn via SWNS

The biggest meat-eating dinosaur that ever lived hunted underwater, according to new research.

Spinosaurus could grow up to 50 feet long and weigh 20 tons - dwarfing T Rex.

Now an analysis of the marine monster's bones has found it was adapted for an aquatic lifestyle.

They were dense - just like those of today's penguins, hippos and alligators.

This provided buoyancy - enabling Spinosaurus and its cousin Baryonyx to submerge themselves to kill.

Meanwhile, another closely-related dinosaur called Suchomimus had lighter bones that would have made swimming more difficult.

So it likely waded like a heron instead - or spent more time on land like other dinosaurs.

Spinosaurus was powered by a fin-like tail - capturing large, slippery fish with six-inch-long razor-sharp teeth.

It lived about 100 million years ago roaming the swamps of North Africa and belonged to the theropods - carnivores that included T Rex.

Lead author Dr. Matteo Fabbri, of the Field Museum, Chicago, said: "The fossil record is tricky - among spinosaurids, there are only a handful of partial skeletons.

"Other studies have focused on interpretation of anatomy, but clearly if there are such opposite interpretations regarding the same bones, this is already a clear signal that maybe those are not the best proxies for us to infer the ecology of extinct animals."

Very dense bones are used as a proxy for aquatic adaptation. Even animals clearly not shaped for it - such as the hippopotamus - have them.

The feature often precedes the evolution of more obvious signs - like fins or flippers.

The international team scanned 380 bones from extinct and living animals ranging from mammals, crocodiles and birds to marine and flying reptiles.

The hunting technique of Spinosaurus has been debated by palaeontologists for decades.

Some have proposed it could swim, while others insisted it was only capable of wading.

All life initially came from the water. Most terrestrial vertebrates contain members that have returned to it.

Mammals are mainly land-dwellers - but whales and seals live in the ocean. Otters, tapirs and hippos are semi-aquatic.

Birds have penguins and cormorants while reptiles have alligators, crocodiles, marine iguanas and sea snakes.

Until recently, non-avian dinosaurs were the only group that didn't have any known water-dwellers.

That changed in 2014 when a new Spinosaurus skeleton was described by Dr. Nizar Ibrahim at the University of Portsmouth.

It had retracted nostrils, short hind legs, paddle-like feet and a fin-like tail - all signs that pointed to an aquatic lifestyle.

Dr. Fabbri said: "The idea for our study was, okay, clearly we can interpret the fossil data in different ways. But what about the general physical laws?

"There are certain laws that are applicable to any organism on this planet. One of these laws regards density and the capability of submerging into water."

Across the animal kingdom, bone density tells whether an individual is able to sink beneath the surface and swim.

Dr. Fabbri said: "Previous studies have shown that mammals adapted to water have dense, compact bone in their postcranial skeletons.

"We thought, okay, maybe this is the proxy we can use to determine if spinosaurids were actually aquatic."

The researchers put together a dataset of thigh and rib bones cross-sections from 250 land and water-dwelling species.

They were compared to fossils from Spinosaurus, Baryonyx and Suchomimus.

Dr. Fabbri said: "We had to divide this study into successive steps. The first one was to understand if there is actually a universal correlation between bone density and ecology.

"And the second one was to infer ecological adaptations in extinct taxa. We were looking for extreme diversity.

"We included seals, whales, elephants, mice, hummingbirds. We have dinosaurs of different sizes, extinct marine reptiles like mosasaurs and plesiosaurs.

"We have animals that weigh several tons and animals that are just a few grams. The spread is very big."

The menagerie revealed a clear link between bone density and aquatic foraging behaviour.

Animals that find food in water have almost completely solid bones. Those of land-dwellers look more like doughnuts - with hollow centres.

Dr. Fabbri said: "There is a very strong correlation. The best explanatory model we found was in the correlation between bone density and sub-aqueous foraging.

"This means all the animals that have the behaviour where they are fully submerged have these dense bones - and that was the great news."

Spinosaurus and Baryonyx both had the sort of dense bone associated with full submersion. Suchomimus had hollower bones.

It still lived by the water and ate fish as evidenced by its crocodile-like snout and conical teeth. But based on bone density it didn't swim.

Other dinosaurs, like the giant long-necked sauropods, also had dense bones. But the researchers don't think they were swimming.

Explained Dr. Fabbri: "Very heavy animals like elephants and rhinos, and like the sauropod dinosaurs, have very dense limb bones, because there's so much stress on the limbs.

"That being said, the other bones are pretty lightweight. That's why it was important for us to look at a variety of bones from each of the animals."

The study in Nature could open the door to discovering more about how dinosaurs lived.

Dr. Fabbri said: "One of the big surprises was how rare underwater foraging was for dinosaurs.

"Even among spinosaurids, their behaviour was much more diverse that we'd thought."

Stories and infographics by ‘Talker Research’ are available to download & ready to use. Stories and videos by ‘Talker News’ are managed by SWNS. To license content for editorial or commercial use and to see the full scope of SWNS content, please email [email protected] or submit an inquiry via our contact form.

You may like

Metals can heal themselves just like ‘The Terminator’

Two-faced star has hydrogen on one side and helium on other

World’s oldest big game hunting weapon found

An espresso a day could keep Alzheimer’s at bay

Being bipolar significantly raises risk of premature death: study

Soccer players who regularly use head more likely to develop Alzheimer’s

Other Stories

Scientists launching spaceship that could help us sail to Mars

The NASA mission will test a new way of navigating our solar system.

Disabled student takes first steps in 10 years on graduation stage

"It was a big success."

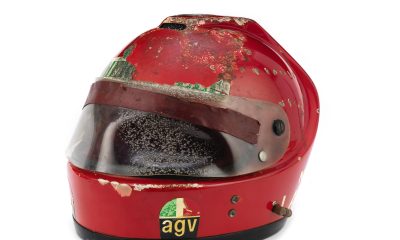

Helmet Formula 1 legend Niki Lauda wore in infamous crash up for auction

Niki Lauda was lucky to survive his burning car in the 1976 incident at Germany's Nurburgring.

Majority of parents ‘customize’ meals for picky kids

Only 15% of parents say their family rule is that kids finish what’s on their plate.

Scientists estimate as much as 11M tons of plastic sitting on ocean floor

Researchers predicted how much plastic pollution ends up on the ocean floor.

Top Talkers

Parenting5 days ago

Parenting5 days agoSingle mom details struggles of feeding her 12 kids

Lifestyle3 days ago

Lifestyle3 days agoWoman regrets her tattoo nightmare: ‘It’s horrendous’

Broadcast7 days ago

Broadcast7 days agoOver 40% of Americans have no clue what a 401k is

Broadcast6 days ago

Broadcast6 days agoHow hard is it for Americans to live sustainably?

Money6 days ago

Money6 days agoOver 40% of Americans have no clue what a 401k is

Pets1 week ago

Pets1 week agoMost cat owners know very little about their feline friends

Environment6 days ago

Environment6 days agoHow hard is it for Americans to live sustainably?

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoDoctors find new use for Barbie dolls in online appointments